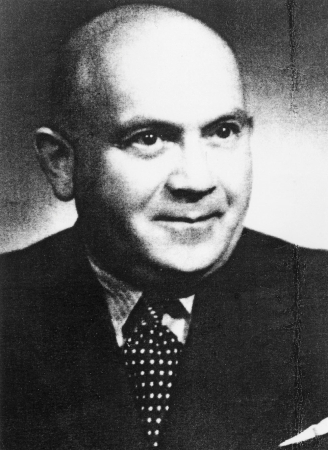

A Halych Physician

This story started to unfold in the Halych region in West Ukraine. Specifi cally, in the then Lemberg, a town nowadays called Lviv. 18 January 1895, Michael Marzell Bohin was born into a Jewish family of Jakub Bohin, a secret Tax Authority council and Bedriska, nee Morgenstern, a teacher.

He attended a primary school and later the Polish grammar school in Lviv. In 1914, age nineteen, Michael enlisted as a medical specialist in the army. Three years later, as a medical service lieutenant, he was awarded the Military Cross of Merit for his defence of Lviv. After the collapse of the monarchy in 1918, Lviv became part of the so-called Second Republic of Poland. Michael started his studies of medicine and, at the end of the second semester, left for Prague where he continued his education at Charles University. (Records show that 25 November 1919 he enrolled in the sixth semester.) He graduated at the age of 27. During the diploma award ceremony, however, he had to sign a waiver of his rights to practise in the CSR because he did not possess citizenship. Fortunately, this changed after his marriage to Ludmila Tobkova (* 19. June. 1896). Before they were wedded, though, Bohin had had to give up his Jewish faith and so he accepted baptism from the hands of a priest from the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren on 15 November 1925. Having completed his studies, he started to work at prof. Houl’s bacteriology Clinique and then in the Na Plesi Sanatorium where patients suff ering from pulmonary diseases were treated. Then he was off ered employment at the 1st Surgical Department at Charles Square, Prague where he met prof. Rudolf Jedlicka, the leading Czech surgeon and founder of Czech radiology. Since 1913, Jedlicka’s name has been tied to the Jedlicka’s Institute and the Prague Sanatorium in Podoli opened in 1914. There, Michael worked in a laboratory. In September 1926, he started to work as a general practitioner in Bilina and the period from 1927 until 1934 as a general practitioner for railway employees in Louny. In 1934, he moved to Prague and opened a private practice in Husinecka St. 2/557, Zizkov. After the declaration of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia on 16 March 1939, he lost his practice as a result of anti-Jewish measures. He and his wife moved to Pribyslavska St. 10. Bohin’s name was recorded on the so-called Zentralstelle name lists that were part of the groundwork for deportations of Jews from the Protectorate. His number was 3662 and since he was a Jew living in a mixedrace marriage, he was not to be subject to repressions— just yet.

In the end, the Central Offi ce for Jewish Emigration di impact his life greatly. He received a mandatory assignment dated 20 January 1943 to go work at a “gypsy internment camp” in Lety near Pisek, where an epidemic of typhus and typhoid fever had broken out. Michael, an expert in infectious diseases, working closely with Dr. Bohumil Stejskal, a physician from the Na Bulovce Hospital, who had also received a mandatory assignment in Lety, managed to stop the epidemic. Later, when the camp was closed in 1943, Michael was moved to a similar site in Hodonin near Kunstat. Finally, after the Hodonin camp had been closed, he returned to Prague and worked as a physician for the local Jewish community. Ironically, 19 October 1944, he was arrested by the Gestapo and taken to the Petschek Palace. From there, he was probably transferred to the Pankrac Prison, and, 25 October, to the Gestapo Prison in the Small Fortress at Terezin. He was taken for further interrogations to Pankrac 7 November and returned to Terezin 19 December. The reason for his arrest had been peculiar in the least. After the Nazis had taken Warsaw over in autumn 1939, they took all the documents from the secret service to Berlin. Five years later someone discovered that a Dr. Bohin, a Polish Jew from Lviv, had provided the Polish consulate with information on the movement of the German army in 1939. This information was passed on to the Prague Gestapo and Michael was charged with espionage. The truth is, Michael’s former schoolmate from the Lviv grammar school was working at the Polish Embassy at that time. Michael had met him before he left the country and his friend took notes on their conversation.

Michael’s stay in Terezin was, once again, brief. 30 January 1945 he, along with other prisoners, was transported to the Mauthasen concentration camp. Coincidently, he made the acquaintance of Czech prisoners who were helping with newcomers. Then, when he was to be transferred to a subsidy camp in Gusen, Czech prisoners who working in the gestapo document department helped him out. They exchanged Michael’s registration card of a Jewish prisoner for a card of a Czech national kept in the so-called protective custody due to political reasons. His data were changed accordingly also in the camp record offi ce. As a result, he was placed into the so-called “sanitary camp” outside the main grounds. There, inspections were carried out only sporadically since the SS soldiers were afraid of getting infected. Michael did survive his imprisonment, and, 19 May, he returned to Prague: weak, exhausted and suffering from diabetes had to spend several weeks in the Vinohrady Hospital. He did survive the war, too. But his marriage did not and of his Lviv family only his brother in law stayed alive. In the early August 1945, Michal resumed his medical practice at his pre-war address. It was probably then that he changed the spelling of his fi rst name to Michal. Many Romani and Sinti people—his former patients—came to see him. In 1947, he was registered as a medical consultant of the CSD and a general practitioner. In November 1948, he married Maria Biokova who was 25 years his junior. She was born in Goslawice, Poland, and after she had received her medical training she helped Bohin as a nurse in his offi ce at Masaryk Railway Station. In spite of the fact that Michael was an educated man with extensive expertise who spoke fi ve languages and published in Swiss journals, he did not do well during the communist era either. In 1950, he was registered just as a physician practising at a railway medical offi ce at Masaryk Railway Station. Dr. Bohin died of heart attack 26 January 1956. On his last journey to the New Jewish Cemetery in Olsany he was accompanied by a number of former Mauthausen inmates, as well as by a numerous crowd of the Romani and Sinti people. His modest tombstone features the following sign in Hebrew: May his soul be bound up in the bundle of life.

Prepared for Terezín Memorial by Luděk Sládek

photo © Alena Hájková Terezínské listy „The Life of Physician Michal Bohin“ (2000); Markus Pape, Romano Janinen 2000 | photo © taken from Terezínské listy (2000); Markus Pape „And no one will believe you“; Federation of Jewish Communities in Prague; National Archive, Luděk Sládek

www.pamatnik-terezin.cz

www.facebook.com/TerezinMemorial

Nesouhlas se zpracováním Vašich osobních údajů byl zaznamenán.

Váš záznam bude z databáze Vydavatelstvím KAM po Česku s.r.o. vymazán neprodleně, nejpozději však v zákonné lhůtě.