Catholic priest and theologian, 33rd Archbishop of Prague and Czech primas, political prisoner of two regimes, Josef Cardinal Beran was born on December 29, 1888. He was the oldest child of the seven children of Josef and Marie Beran. On Saturday January 9, 1889 he was baptized in the Pilsen Cathedral of St. Bartholomew, 21 May 1898 he was present at Holy Communion and he was present at confi rmation on 13 October 1902.

The modest conditions of the teacher‘s family, where he grew up, gave him faith in God and also the national feeling, which was shown in love for the literature, homeland, nature and music. His father was an example of strength of character, principality, self-discipline and consistency. From his mother he inherited kindness, optimism and artistic tendencies. After he had fi nished studies at fi ve-year general school in Pilsen, he attended eight classes of the classical grammar school (1894–1899), where he was one of the better average students. He did not think about becoming a priest. At fi rst, he was attracted by a military course like the other students of Pilsen‘s cadets, later he wanted to help people and study medicine. Prof. Kudrnovsky, who taught religion at grammar school and lectured at Charles University, told his student Beran that he would recommend him to study in Rome because he saw all the characteristics and intellectual prerequisites for the priesthood “Even though I was not entirely decided for priesthood, I could hear the calling of God‘s voice in my soul more often, and I could hear that voice more frequently during higher grammar school.”

Therefore, he decided to study at the Czech college of the Pontifi cal University in Rome, which was located in Via Sistina before the World War. Here he studied Italian and Latin, where he went through thorough training of dogmatics, fundamental theology and ecclesiastical history. He was successful in his studies and won his fi rst prize unexpectedly in singing. He obtained his Bachelor‘s degree 30 November 1909 and joined the III. Order of St. Dominika, where he accepted the monastic name Thomas. He was consecrated in the fourth year of his studies at the Pontifi cal University of De Prapaganda Fide and received his ordination on 10 June 1911 in the Basilica of St. John the Baptist. He served at his fi rst mass in the Church of St. Jan Nepomucký at the Czech College a day later. He received one of the higher academic titles – the licentiate on 2 December 1911 and he fi nished his fi ve years of studies with a doctorate in theology on 26 June 1912.

After his return home he served his fi rst mass on July 5, 1912 in the cathedral of St. Bartholomew in Pilsen.

His fi rst chaplain place was Chyše u Žlutic, followed by Prosek, which was still near Prague at the time, where he joined in January 1914 as the second chaplain and catechist in the general school in Vysočany. The First World War broke out and Beran was transferred to Michle, where he was from August 1, 1914 to July 31, 1917. The sanctuary of St. Joseph‘s Deaf-mute patients in Krč belonged to the pastoralism, where Beran assisted the nurses from the Notre Dame Congregation of School Nurses and advised them on how to deal with these patients. Here his pedagogical and psychological abilities were fi rst demonstrated. He could further develop these abilities at St. Anne women’s teaching institute in Ječná Street (1917–1928). The sisters of the congregation administering the Teaching Institute suggested to the director that he should appoint Beran as the local catechist. When Charles University in July 1917 acknowledged the validity of his Roman doctorate, he accepted the off ered position. After the director of the institute retired, Beran became his successor in September 1925. Two years later, he was appointed Archbishop‘s Notary due to his merits. From 1928 he taught pastoral theology at the Faculty of Theology of Charles University. Still, he continued to pursue his mission in the Krč sanctuary, among the underprivileged people in Kobylisy, to publish, to translate and to become a sought-after confessor. The representation of the Theological Seminary addressed him with the off er to take on the role of a confessor in the Seminary Church of St. Vojtěch in Prague Dejvice. Since 1929 he was an assistant professor at the Catholic Theological Faculty of the United Kingdom and on 20 April 1932, he defended his lectureship. Since October 1934 he was given a canonical mission for the fi eld of pastoral theology. He was appointed Rector of the Prague Archbishop‘s Seminary in 1933.

After the arrival of the Nazis and the proclamation of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia on March 16, 1939, the Czech Faculty of Theology functioned until October 1939. During the celebration of the emergence of the Republic of Prague, the death of Václav Sedláček and above all Jan Opletal, in the anti-communist demonstration the Nazis closed the Czech universities. Rector Beran got to the Gestapo viewfi nder for what he was and what he was imagining.

During the celebration of the Republic, Prague was shaken by the death of Václav Sedláček and above all Jan Opletal, whose funeral grew up in an anti-communist demonstration, and the Nazis closed the Czech universities. After the assassination of Heydrich (27 May 1942) there were extensive arrests of the Czech population. The reason for the arrest of Rector Beran was most likely his serving at the Mass for the imprisoned Czechoslovak offi cers, which played the Saint Wenceslas Chorus and the Czechoslovak anthem at the end. The Gestapo came to Rector Aran on June 6, 1942. There was a house search, hard interrogation and imprisonment in the Pankrác Prison. He was almost certain that the fate of the hundreds who had been executed awaited him. “I was imprisoned with one man who was an enthusiastic follwer of Masaryk and Beneš. He knew he would be executed, which we all˝expected. He had a family and children, and he was so distressed that we were all saddened by it. We tried to comfort ourselves and comfort him, and God knows how hard it was. He did not think about God or at least he did not indicate that he did, and he expressed his devotion to the two presidents, saying: Before he shoots me, I will say: Let the Czechoslovak Republic live, let Beneš live! I do not know how much power this had given him, but when they came for him the next day, he walked away hearty. My soul was full of sorrow. About an hour after his departure, perhaps in the moment when he was shot, a blackbird arrived at the window of our cell. He sang sadly and fl ew away. I was sick, I think I was crying, and I prayed for him all night. I had to force myself with all of my strength to forget everything I had left out there: a seminar, a mother, my loved ones, everything. I had felt that if I had immersed myself in the memories of my loved ones, their pain and tears that I would lose control and that I would not be myself. That inaction, that month of waiting for death, the uncertainty of what was going on out there would have been enough to overcome me had it not been for the strength gracious God gave me. It was the prayers and the persistent sacrifi ces of my dear ones that worked for me.”

After several interrogations and the imposition of “guardianship”, he was transferred from the Pankrác Prison on 1 July 1942 to the Gestapo Prison in the Small Fortress of Terezín. Slavery, hunger, deplorable hygiene, overcrowded cells, insects, illness, and torture of wardens made life in prison inhumane. In addition, Jews and clergy received “special treatment”. Rector Beran was included in the so-called Baukomanda for turning quarry stone into gravel. “I was weak, so I could barely lift my hammer. After every hit, I thought I would fall down and die. I sacrifi ced everything for those who were dragged into the gas chambers that day and did not return to us that night” he recalled. In cell No. 12 he met a man who would become a cardinal in the future, Salesian priest Štěpán Trocht, who, in memory for the Terezín Memorial described one of the daily realities. “It was a rainy and merciless day. Jews were carrying gravel. There were not enough Jews and they were searching for the rector of the Prague seminar. He was taken from a cluster of prisoners and sent to a heavy carriage. That fi rst day was terrible, the day of horror, killing and beating. I admired the supernatural calm and silent patience of Monsignor Beran. He quietly prayed and gave me courage: “Do not be afraid, Stepan, the Lord sees it – it will all be good.” Cardinal Trochta also recalled how one day a guarder Albin Storch (the sadist, right hand of the camp commander and always drunk), who commanded a group of prisoners, the so-called Storchkommand, was aggressive.”We have experienced a great killing of a Jew. Storch threw a half-dead Jew in front of the the carriage while we were carrying down the slope. We could not stop the carriage. I took the risk and barely succeeded in moving the Jew at the last second so the carriage did not hit him. When we were coming back, the half-dead Jew lay in the ditch, his mouth full of clay and hay. I thought he was already dead. But at the afternoon‘s call he was brought back alive. In the afternoon, Stephan Rojko fi nished him off .” The small fortress of Terezín was only a transfer station for Rector Beran. Within two months of his arrival, on August 31, 1942, he was deported to the Dachau concentration camp, where the Nazis concentrated 2,740 “dangerous” clergymen from 134 dioceses and 24 nations during the war. The transport arrived at the Dachau railway station on September 4, 1942. In the reception offi ce with Beran, they fi lled out the questionnaire, took fi ngerprints, took a photograph and placed it in the Schutzhäftling, Geistlicher category. On the penal mundour, the red triangle was “political” and was given to the Czech priesthood block 28 as the number 35 844. Priest František Štverák recalled: “In Dachau, he experienced the purifi cation of the earth. The crude capo threatened to have him fl own through the chimney. Even though he was not doing well at all, he shared the food packages with his fellow prisoners he received and did not hide (Stverák), he would give away everything. No one ever heard Beran complaining, crying, and despair: Stay calm men, everything will end well. Saint Joseph will decide things” he used to say.” In January 1943 the epidemic of the belly typhus broke out in the camp, which also infected Rector Beran. He returned from the hospital, weighed 49 kg, but with the help of his friends and camp solidarity, they managed to temporarily reassign him to the camp for the disabled where he mended socks. After he recovered, Beran made a lifetime promise: “If I return to my homeland, I will try not to deny anybody help and if it is in my power, and will not contradict the will of God, I will do everything that I am asked.” Rector Beran spent nearly three years in Dachau before the camp was liberated on April 29, 1945 by the Americans. After the repatriation of former Czech prisoners on May 21, 1945 he could return to his homeland.

After he got back from Dachau, he returned to management, was appointed

Vice-Chancellor of the Catholic Action, a representative of the Prague Ordinary of the Catholic Charity and at the beginning of the semester (1945) he was appointed regular professor of the Catholic Theological Faculty of the Charles University. Pope Pius XII. appointed him on 4 November 1946 by the 33rd Prague Archbishop since the times of Arnošt from Pardubice. On Sunday of the same year, he accepted the episcopal consecration in the Cathedral of St. Vít in Prague. In his role he advocated for the return to Christian values, reconciliation, cooperation and solidarity. He became a moral authority of the country. Since 1947, he faced increasing pressure from communists who have no interest in co-operating with the Church. After the Communists took power in February 1948, political opposition and democratic elites were eliminated, and the regime focused on the Catholic Church. Archbishop Beran faced an escalating repression against the Church, insisting on respect for its internal autonomy. The Episcopal Conference, chaired by Archbishop Beran, banned the priests from running for election, but Chaplain Plojhar did not obey and ran for election on May 30, 1948, and took a seat in the Communist government. Archbishop Beran suspended him and excommunicated and never took the excommunication back. On Saturday, June 18, 1949, Archbishop Beran made his last speech to the people at the Basilica of the Virgin Mary in Strahov: “I do not know how many times I will still be able to speak to you, but I now declare publicly as a bishop. Never, ever, will I call for an agreement that is against the laws of God and the holy Church. I swear as a bishop, I will never betray the laws of God and the holy churches. It hurts me very much that my Czech people will be persecuted because of me. But I can act no other way.” On the second day of the Holy Mass in the Holy Trinity Temple, two-thirds of the Communists declared that the “Catholic Action” was not Catholic, and the Catholic “Catholic epistles” occupied by the Communists were not Catholic. After Mass, he was supposed to go up on the balcony of the archbishopric and speak to the believers. But the StB prevented him from do so by pretending to “protect him” in front of the crowd. In the second half of June 1949, the Archbishopric held a confi dential meeting of bishops in Prague, which was uncovered, and the StB burst into the palace. Since then, the Archdiocese of Prague had been cut off from the outside world and Rome, and the Communist regime tried to destroy the Church in our country. At that tense time, sometime in March 1950, the archbishop secretary of monsignor Boukal addressed Zdeněk Sternberg‘s students of law, who remembers: “Archbishop‘s secretary of monsignor Jan Boukal – somebody must have tipped him off – he wrote me three lines, an envelope without an address placed in a drawer in my apartment in Malá Strana. We met up, even though I was a little afraid because even in the church it was all sorts. The Archbishop wrote a report on the state of the Church in Czechoslovakia for the Holy See, and I asked if I could get it across the border to a Bavarian monastery. I agreed. I‘m not saying that it was from some heroic impulses, but rather as a young man without any scruples, I blurted out “monsignor, I‘ll deliver it myself.” With Matějka, with whom I crossed the border crossings, we drove a Harley Davidson machine in the direction of Tachov. The trip was quite harsh, it was raining, we even came across a patrol with a dog. It was terrible. At the Šumava border they brought a priest from the Bavarian side, and I gave him the sealed envelope, instructing him to deliver it to Rome. I went back alone and experienced one of the worst moments: At 2 am at night imagine you are going through a thick dense forest and do not know if you will fi nd the way back. It turned out well. We found our motorcycle and drove home. In one pub, where we stopped for some tea, the door suddenly opened, three secret agents came in, separated us and interrogated us. But we had already agreed what we would say if such a situation occured, so they let us go. In the morning we were happily back in Prague.” (The sister of Mr. Sternberg Karolin, a year younger than him, was the fi rst of nine siblings to marry.) It was in 1947 and her wedding with Maxmilián Wratislav of Mitrowicz took place in the castle in Bohemian Sternberk. The Archbishop Beran wed them notes the author of the book.) Thus, they learned in Rome about the situation of our Church and the Archbishop of Prague.

The period of sixteen years of illegal internment of Archbishop Beran began. The conditions of life in it, in many ways, resembled the prison regime, but they were characterized by total isolation from the outside world and total loss of privacy. Beran stayed In Roželov u Rožmitál from 7 March to 2 April 1951. Josef Beran recalled: “We stayed for about three weeks Roželov. I was informed that abroad they already knew that I could be killed. They even accounted the Communists for the fact that I had to move away. It was about ten o‘clock in the evening and at about midnight we drove to the town of Rozenthál near Liberec.” I stayed in Růžodol near Liberec from April 2, 1951 to April 17, 1953. After that I was sent to Myštěves (April 17, 1953-1957) and Paběnice near Čáslav (December 20, 1957 – October 3, 1963). The StB tried to get the local nuns to cooperate against the Archbishop, who responded as follows: “They are not allowed to accept the truth. They will listen to you, and your opinions which will make them have a bolder approach towards you. They know well what we are, what we wanted and should have done. They have silenced us. Now is the time of their haughtiness before their time is up. God with you, sisters. “ He transferred to Mukařov near Prague where he stayed from October 3, 1963 to May 2, 1964, and then transferred to Radvanov near Mladá Vožice, where he stayed until 19 February 1965. In Radvanov he received report of his appointment by the Cardinal on January 25, 1965. The complicated negotiations of the Holy See with the Communists resulted in a regime off er to allow Beran to leave for Rome to be named a cardinal, without the possibility of return. In exchange, the communists agreed with Bishop František Tomášek as administrator for the collaborating vicar Antonín Stehlík. Beran was put against a diffi cult choice. He decided, however, to bring this sacrifi ce in the interest of the local church, and to “voluntarily” become an expellee. He left for Rome on February 19, 1965.

Shortly after arriving in Rome, he was promoted to cardinal by Pope Paul VI. on February 22, 1965. To the displeasure of the domestic regime, Cardinal Beran “at rest” still went to work immediately. He spoke at the Second Vatican Council on September 20, 1965, where he gave his famous speech on religious freedom. He surprised others by his vitality, optimism and tenacity. He chose Nepomucenum in Bohemia as his residency, which he lifted up not only with his presence. He went on pastoral journeys to France, Switzerland, Italy … and the journey to the USA increased his general enthusiasm. František Schwarzenberg welcomed the speaker in the following way: “The greatest living son of Czech country, who lives in freedom and in prison, at home in his own and in the open world, always comes to serve faithfully, and he will still serve God, his country and the nation, is coming. “For the money he had earned abroad, he bought a pilgrimage house of Velehrad in Rome, which sheltered exile Catholic organizations. He spoke to the faithful ones” behind the iron curtain” of the Vatican Radio, he provided the publication of books and magazines for Czechoslovak Catholics. In 1968, he wanted to attend the World Eucharistic Congress in Bogota, Colombia, but his journey ended in Germany, where doctors found a large bowel cancer in his body. As soon as Beran had recovered after the operation, he continued the work at publishing and pastoral centers of Velehrad. In the same year, the medical examination confi rmed the fi nding of advanced lung cancer in his body. The report on the occupation of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 did not contribute to his already poor health. When student Jan Palach died on January 19, 1969, and on January 20, Prague celebrated his memory, Cardinal Beran made a speech in the Vatican Radio, where he said by the way: “I mourn with you over the death of Jan Palach and others who died in a similar death like him. I bow before his heroism, though I cannot approve of his desperate act. The killing is never human, so no one shall ever repeat this …”

His last Mass he served in Nepomucena on 17 May 1969, he was completely exhausted and the doctor, he was called, said Josef Beran was dying. After receiving the sacrament, the anointing of the sick, priests and theologians gathered at his place and he blessed all present. Pope Paul VI. hurried to his bed, since he wanted to catch him alive, but he was late. So, just as peacefully as Joseph lived, he also left this world so. The Communist government did not allow the transfer of his remains to his homeland because they feared a civil unrest. His remains were deposited in the crypt of the temple of St. Petra in Rome. As Pope Paul VI. decided, the Archbishop of Prague and the Primate of Bohemia Joseph Cardinal Beran was buried in the crypt of the temple of St. Peter in Rome.

Cardinal Beran‘s ultimate will, however, has been fulfi lled. His remains were 19 April 2018 picked up from a temporary sarcophagus and the following day they were transported home, where bells rang all over the country after landing. The remains were subsequently placed in a sarcophagus in the chapel of St. Anežka Česká in the main ship of the Cathedral of St. Vít. In 1991 Josef Beran was in memoriam awarded with the order of Tomas Garrigue Masaryk of the fi rst class and on April 2 1998 the process of his beatifi cation began.

For Památník Terezín Luděk Sládek

poděkování: Stanislava Vodičková ÚSTR, pan Zdeněk Sternberg, Arcibiskupství pražské

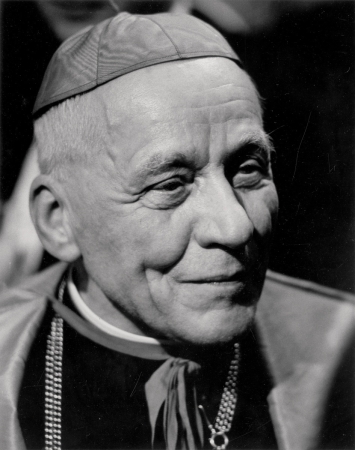

foto: Kardinál Josef Beran, 10. 3. 1966 © archiv RNDr. Jiřího Bauma

www.facebook.com/TerezinMemorial

www.pamatnik-terezin.cz

Nesouhlas se zpracováním Vašich osobních údajů byl zaznamenán.

Váš záznam bude z databáze Vydavatelstvím KAM po Česku s.r.o. vymazán neprodleně, nejpozději však v zákonné lhůtě.